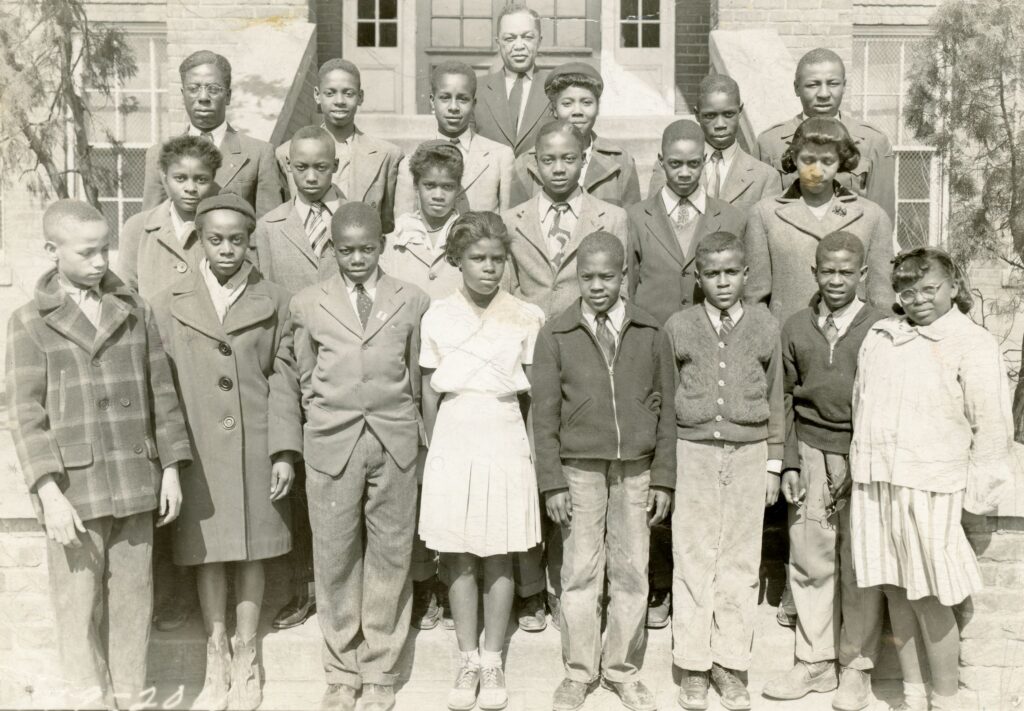

Education for African Americans was limited prior to 1865 and segregated until after 1955. Because African Americans living in Gainsboro and Northeast Roanoke valued education as an essential life skill, they insisted that their children become well educated for survival and economic prosperity. Black citizens pursued investment in schools to serve their community and recruited Black teachers. Often, religious institutions and leaders took on roles for advancing education and facilities, lobbying local officials for upgraded facilities, and sometimes offering churches for instructional use.

Limited Educational Opportunities before 1870

Before the late 1800s, the ability of African Americans in the United States to access education was very limited. Blacks in urban areas in the North had more educational opportunities than did Blacks in the South. White leaders in the South actively discouraged education of African Americans because they feared the ability to read and write would encourage enslaved people to organize and rebel.

It was very difficult for African Americans to become educated in Virginia prior to the Civil War. In 1831 the General Assembly prohibited African Americans, free or enslaved, from meeting in a school-house, church, or other place for the purpose of teaching reading or writing. Nevertheless, some Black Virginians did learn to read and write, often becoming religious, educational, and civic leaders in their community.

Black Teachers Rise to the Occasion

As early as 1861, free African Americans in Virginia were eager to establish schools and increase literacy. From 1865-1870, the Freedmen’s Bureau was charged with resolving various problems created by the war, including educating newly freed African Americans. However, the bureau was not authorized to spend money on teacher salaries, books, or classrooms. Instead, it encouraged Black communities to raise money to purchase land, build school buildings, and pay teachers.

Local Black citizens took the initiative and raised money for schools, assisted by Northern missionary organizations and freedmen’s aid societies. Similarly, teachers included educated Black Virginians, who now could teach publicly, as well as teachers from the North, both white and Black, who came to Virginia to help establish African American Schools.

More on educators in Gainsboro

Public School System Established in 1870

After the Civil War, Virginia adopted a revised state constitution which included provisions for public schools throughout the state. In 1870 Virginia enacted legislation that established a public school system supported by state tax revenue, authorized counties to levy additional school taxes, and—over the objections of African Americans serving in the state legislature at the time—required schools to be racially segregated.

“White and colored persons shall not be taught in the same school, but in separate schools, under the same general regulations as to management, usefulness, and efficiency…” —Section 47, Schools and Education, 1870 Acts of the General Assembly

A Century of Segregated Schools

When Roanoke County set up its public school system in 1870, six of twenty-three schools were set apart for “Negroes”—including one in Big Lick. Until August of 1884 schools were maintained by the County of Roanoke.

Roanoke City’s first public schools were established in 1884, in accordance with the city charter. City Council appointed a school board and adopted an ordinance specifying 15 cents out of every $100 of assessed value of real estate and personal property be allocated to the “public school fund.”

By 1884, with the rapid growth in Roanoke of employment opportunities, overall population, and its Black population, the Gainsborough School was overcrowded, serving 200 pupils. For several years additional space was rented to accommodate the overflow of students. This included rooms in neighborhood churches, as well as a building on Shenandoah Avenue owned by the Roanoke Land and Improvement Company. To ease overcrowding and makeshift facilities, Roanoke citizens approved a bond issue to construct a new school for Black students in 1887.

-

- Old Lick School (1872), was the first public school for African Americans in the Town of Big Lick. It was a log building located on Dasher (Diamond) Hill just off the old Lynchburg-Salem Turnpike (now Orange Avenue).

-

- Gainesborough School (1875) replaced the Old Lick school. It was a larger, two-room, frame building located between Hart and Douglas Avenues. When the school closed, the property was sold for $25. The money from the sale was used to fence the African American cemetery subsequently located on the lot.

-

- First Ward Colored School (1888) was built on Shenandoah Avenue, west of Jefferson Street, near the Railroad Depot, and replaced the 1875 Gainsborough School. Its first principal was Lucy Addison. The school ceased operation before 1892.

- Gainsboro School/Second Ward Colored School (1889) was constructed west of North Jefferson Street on Gainesboro Road (1st Street, NE) at the corner of Seventh Avenue, NW (Rutherford Avenue). According to the 1889 City Directory, the school housed 350 pupils, the principal was D. W. Harth, and the assistant principal was Lucy Addison. Gainsboro School operated until 1958 when it was demolished for urban renewal.

-

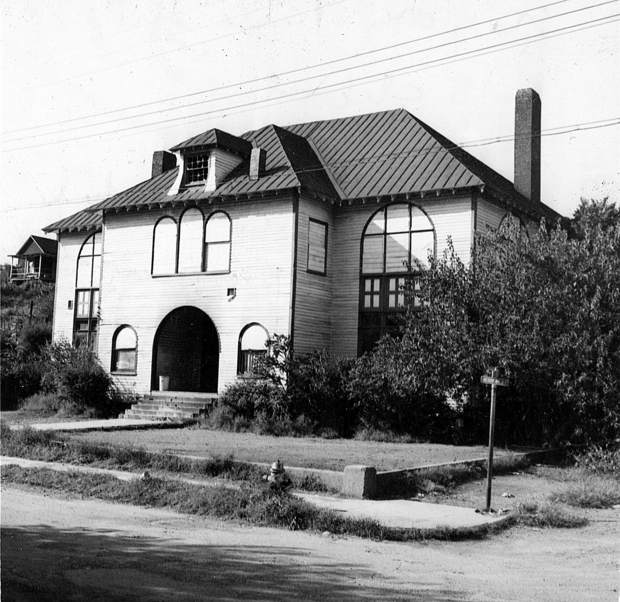

- Gregory School/Third Ward Colored School (1892) was located on Gregory Street at 6th Street, NE. The school opened with a faculty of four. The first principal was T. T. Henry, followed in 1898 by John R. Dungee. At the turn of the century, the first vocational classes for Black students were organized at the Gregory School. The Gregory School served the Black community through the early twentieth century and was demolished as part of urban renewal.

-

- Gilmer School, originally constructed for white students, was assigned as a school for Black students in 1935. Located on Fourth Avenue, NE (Gilmer Avenue) between 3rd and 4th Streets, NE, the school was demolished for urban renewal in the 1960s.

-

- Harrison School (1917) located in the 500 block of Harrison Street, NW, began as an elementary school through grade 7, with 14-rooms, 17 teachers, and over 600 pupils. Students desiring additional education had to attend schools outside Roanoke. Under the leadership of principal Lucy Addison, the school facilities and curriculum were expanded for additional grades.

- In 1924 Harrison School became accredited as a high school, with its first graduating class that year. In 1928 high school instruction moved to newly constructed Lucy Addison High School. Harrison School then operated as an elementary school until it closed in the late 1960s as a result of desegregation. Its closing devastated the community, who had fought to keep it open as a neighborhood school. When the building was threatened with demolition, neighborhood residents spearheaded the effort to save it, which resulted in its reuse as senior housing and a cultural center.

- Harrison School (1917) located in the 500 block of Harrison Street, NW, began as an elementary school through grade 7, with 14-rooms, 17 teachers, and over 600 pupils. Students desiring additional education had to attend schools outside Roanoke. Under the leadership of principal Lucy Addison, the school facilities and curriculum were expanded for additional grades.

- Lucy Addison High School (1928) was first located on Douglas Avenue, NW. Named in honor of pioneer educator Lucy Addison, the school was the first public building in Roanoke named for a Black leader. In 1952 Lucy Addison High School moved to a new building on Orange Avenue at 5th Street, NW. With the integration of Roanoke’s public schools in 1973, it became Lucy Addison Junior High School.

-

- Booker T. Washington Junior High School (1953) was established in what was the former (1928) Lucy Addison High School building on Douglas Avenue. In 1973, as a result of desegregation, the building was converted to administrative offices for Roanoke City Schools. The historic building still stands on the north hill overlooking Orange Avenue.

Sources

Baist, G. W. (1889). 1889 Map Roanoke and Vicinity [Map]. Roanoke Public Libraries, Virginia Room, Roanoke, VA. United States.

Bly, A. T. (2021, Apr. 26). Slave literacy and educaiton in Virginia. Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-literacy-and-education-in-virginia/

Butchart, R. E. (2020, Dec. 7). Freedmen’s education in Virginia 1861-1870. Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/freedmens-education-in-virginia-1861-1870/

Davis, J. (2014, Feb. 3). Black Roanoke: Our story. City of Roanoke. https://www.roanokeva.gov/DocumentCenter/View/1537/Black-Roanoke-Our-Story?bidId=

Dickens, T. (2019, Feb.) Harrison School. Roanoke Times Discover History and Heritage Magazine. Roanoke Times.

Johnson, R. R., Jr. (2015). The Addisonians: The experiences of graduates of the classes of 1963-1970 of Lucy Addison High School, an all-Black high school in Roanoke, Virginia [Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech]. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/72900/Johnson_RR_T_2015.pdf;sequence=1

Julienne, M. E. & Tarter, B. (2021, Dec. 13). Public school system in Virginia, establishment of the. Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/public-school-system-in-virginia-establishment-of-the/

Kneebone, J. T. & Dictionary of Virginia Biography. (2021, Dec. 22). Lucy Addision, (1861-1937). Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/addison-lucy-1861-1937/

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. (2005). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Gainsboro Historic District, 128-5762. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/128-5762_GainsboroHD_2005_final_nomination.pdf

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. (1982). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Harrison School, 128-0043. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/128-0043_Harrison_School_1982_Final_Nomination.pdf

Warren, I. M. (1941) Our Colored People, Our Negro Population: Evolution of Public Education. Federal Writers’ Project.

Worrell, A. L. (1940). The Schools of Roanoke. Federal Writers’ Project.