The Salt Licks

A number of salt licks were located in the semi-marshy areas along creeks in what became Roanoke. Springs with high mineral content ran into these areas when waters were high. In drier periods minerals were left in the soil, and attracted animals and game, such as buffalo and elk, who came to “lick salt.” One of these licks, “Long Lick,” was located between Salem and Campbell Avenues, running from about First Street/Henry Street to I-581. A larger lick, called “the Big Lick,” was found to the east, along Tinker Creek.

These places where animals congregated were noted by the region’s Indigenous peoples, who tracked and hunted them. Paths developed as prey and hunters moved through the valley. When Europeans first explored the Roanoke Valley in the 1600s, they found settlements of the Tutelo (or Torero) people. But by the time European settlers arrived in the 1700s, only the occasional hunting party of Cherokee or Shawnee passed through the region.

European Settlement of the Valley

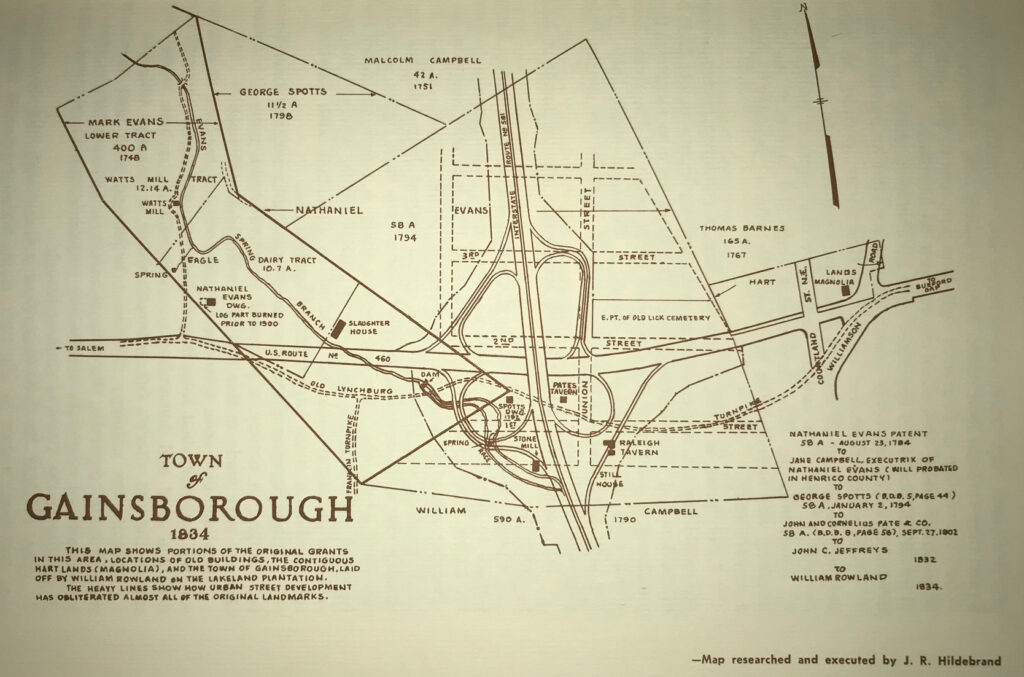

The paths established by game and hunters were the precursors of the roads European settlers used and improved as they migrated through the area. By the early 1800s, two wagon roads passed near what became Gainsboro. One ran north to south, a spur of the Great Wagon Road that brought settlers from Pennsylvania to North Carolina. The other ran east to west, connecting Lynchburg to the Wilderness Road, which ran through the Cumberland Gap and into Kentucky.

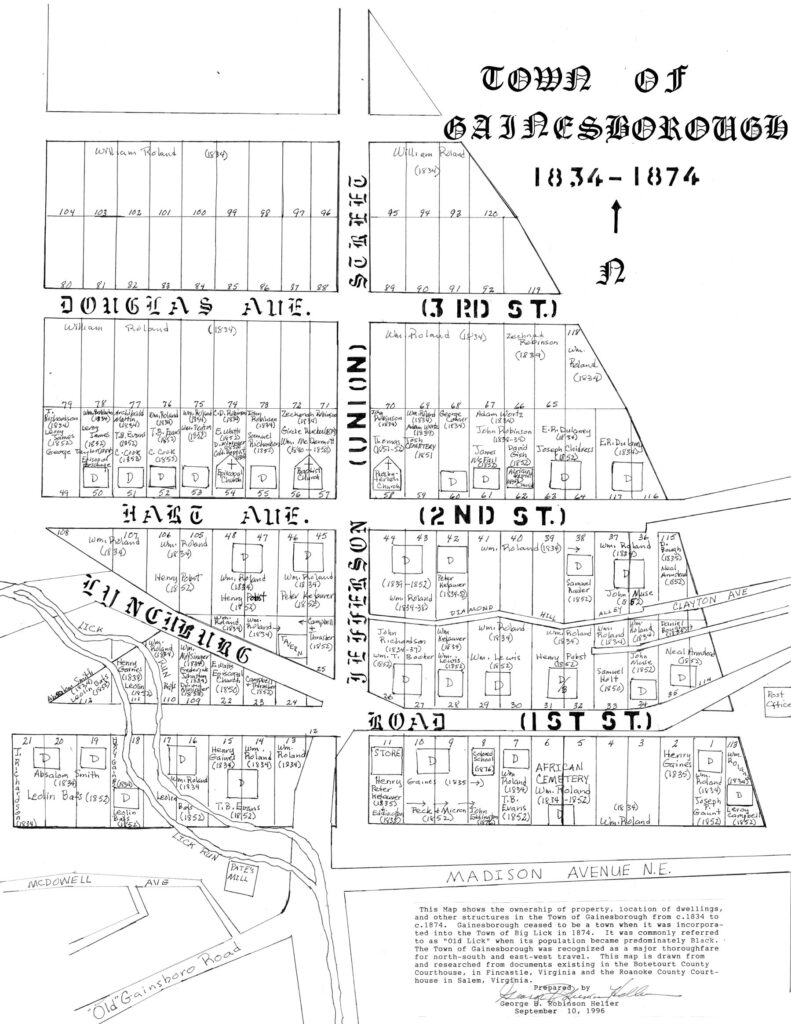

Town of Gainesborough

At the crossroads of these two paths, what is now approximately the interchange of I-581 and Orange Avenue, a town developed, and was often called by “Big Lick” after the nearby salt licks. The passing traffic led to the establishment of a mill, tavern, and store. Then, in 1834 William Rowland laid out a plan of lots on 68 acres of land and held an auction to begin selling them. He named the development “Gainesborough” after Major Kemp Gaines, who assisted Rowland in the venture. Area residents petitioned the General Assembly for a charter for a town by that name, which was granted in 1835.

Within a few years of its establishment, Gainesborough had developed into a busy community of homes, stores, churches, a tavern, and a blacksmith shop. Tinker Creek Baptist Church was established in 1840, and Episcopal and Presbyterian congregations in the 1850s. Dr. Charles L. Cocke, the first president of Hollins College, held a Sunday School for enslaved persons in the Baptist church. In 1838, when the County of Roanoke was established, there were about 10 buildings in Gainesborough; by 1855 there were 29. Throughout this period, the names Gainesborough and Big Lick were both used to refer to this crossroads.

The lands around this small community, including what became the Gainsboro neighborhood to the south, were farmland during this period. In 1750 John Smith became the owner of about 400 acres south of the Great Road (Orange Avenue). Subsequent owners of this property, which encompassed much of today’s Gainsboro, were Malcolm Campbell and his sons William and Archibald Campbell. Fields around Gainesborough were used to grow wheat, hemp (for ropes), and tobacco.

“The country surrounding the marshes was fine farming land and some of as pretty fields of corn and wheat as I have ever seen grew where the Hotel Roanoke and the N & W General Office Buildings stand.”

recalled Henry S. Trout, born in 1841, reminiscing in 1913. — R. P. Barnes, A History of Roanoke (1968), p. 64.

In 1852, the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad completed its tracks and established the Big Lick Depot about one mile southwest of Gainesborough/Big Lick. Subsequent growth and the town center shifted to the area around the Big Lick Depot. The town at the intersection of the Philadelphia Road and the Great Road became known as Old Lick.

Yet, Gainesborough/Old Lick also continued to expand and attracted growing numbers of African Americans. The Episcopal Church building was sold to the Black congregation of the First Baptist church. The 1880 Census indicated 272 Black and 67 White residents in this neighborhood.

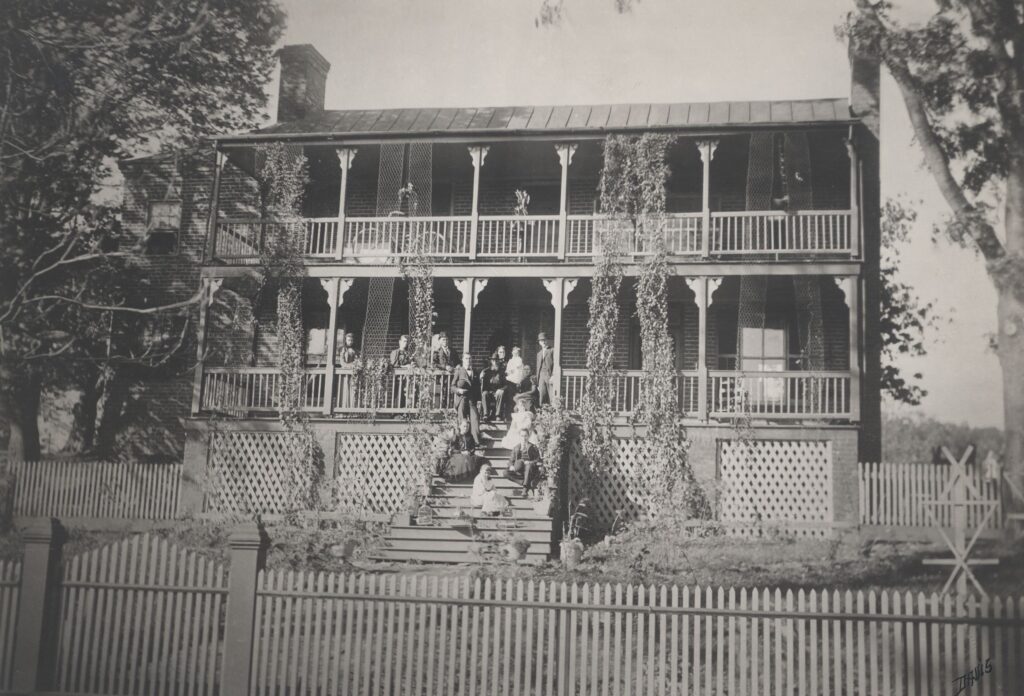

Magnolia Tavern

To serve the travelers passing through the region, Zachariah Robinson built a 2-story, 12-room brick tavern on 6.5 acres he purchased in 1837. After passing through several other owners, the building became known as “Magnolia.” In 1876 Dr. Henry C. Hart established a facility to treat patients with hydro-therapy in the structure.

Sources

Barnes, Raymond P. (1968). A History of The City of Roanoke. Commonwealth Press.

City of Roanoke. (2003, March). Gainsboro neighborhood plan. https://www.roanokeva.gov/DocumentCenter/View/1232/Gainsboro?bidId=

Indians A.D. 1600-1800. (2018, May 14) Virginia Department of Historic Resources. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/first-people-the-early-indians-of-virginia/indians-a-d-1600-1800/

Kagey, D. (1988). When Past is Prologue: A History of Roanoke County. Roanoke County Sesquicentennial Committee.

National Park Service. (2005, November). Gainsboro Historic District (No. 05001276).

White, C. (1982). Roanoke 1740-1982. Roanoke Valley Historical Society.