Biracial Committee

Unlike other communities in the South where civil rights issues were pursued more forcefully, integration in Roanoke proceeded conservatively, peacefully, and collaboratively for almost a decade. In 1960, a Biracial Committee of at least a dozen Black and White leaders met behind the scenes to further peaceful discussion, understanding, and change. From 1960-1968, the Committee of influential ministers, doctors, attorneys, and business leaders engaged in furthering civil rights and change in schools, business services, and employment. Additional members may have been recruited during this period to assist the committee in resolving issues.

“I feel very keenly that we should negotiate as far as possible with those in authority…those with their feet on our necks.”

—Rev. R. R. Wilkinson, cited in his Roanoke Times obituary (1993)

Some of the Black members of the Biracial Committee were:

-

- Rev. Raymond R. Wilkinson – President of NAACP, pastor Hill Street Baptist Church, community activist and leader, and organizer of the Biracial Committee

- A. Byron Smith – President A. Byron Smith Oil Company, real estate broker, civic leader

- Rev. Emmett Green – pastor First Baptist Church, education advocate (father of Cynthia Green, plaintiff Green v. Roanoke School Board, 1962)

- Lawrence Hamlar – owner/founder Hamlar Curtis Funeral Home, businessman, civic leader

- George P. Lawrence – attorney

- Dr. Maynard Law – Burrell Hospital physician, civic leader

- Dr. Harry T. Penn – dentist, civic activist, member of Roanoke School Board

Some of the White members of the Biracial Committee were:

-

- G. Frank Clement – President Shenandoah Life Insurance, civic leader

- John Hancock – President Roanoke Electric Steel, civic leader

- William A. Lashley – businessman, public relations, Norfolk & Western Railroad

- Ben F. Parrott – attorney

- Gordon Willis – businessman, owner Rockydale Quarries

- Arthur Taubman – President Advance Auto, civic leader

- Dr. Dwight E. McQuilkin – educator, Superintendent Roanoke City Schools

Some Roanokers felt that this approach ultimately delayed actions to address racial inequalities. However, members of the Biracial Committee were confident of their unified approach and the ultimate results of improved racial relations. They successfully achieved peaceful integration of schools, businesses, and places of employment.

“Some black leaders, however, called the committee a ‘pacifier’.”

— Roanoke Times, Roanoke Reborn, p.18

Desegregated Schools for Roanoke

The segregated school system in Roanoke resulted in deficiencies and inequalities for the Black schools in Gainsboro. In 1957 there were deficiencies and inequalities. Gainsboro School had no indoor plumbing and was heated by wood stoves. Parents protested the significant overcrowding at Gilmer School (previously a white school) and Loudon Elementary School.

In 1958 Roanoke City voters narrowly approved an $8 million bond issue for building upgrades for both White and Black schools. This was due to an atypical alliance between White Southwest Roanoke and Black Northwest Roanoke, where residents of both areas lobbied for needed improvements in their neighborhoods.

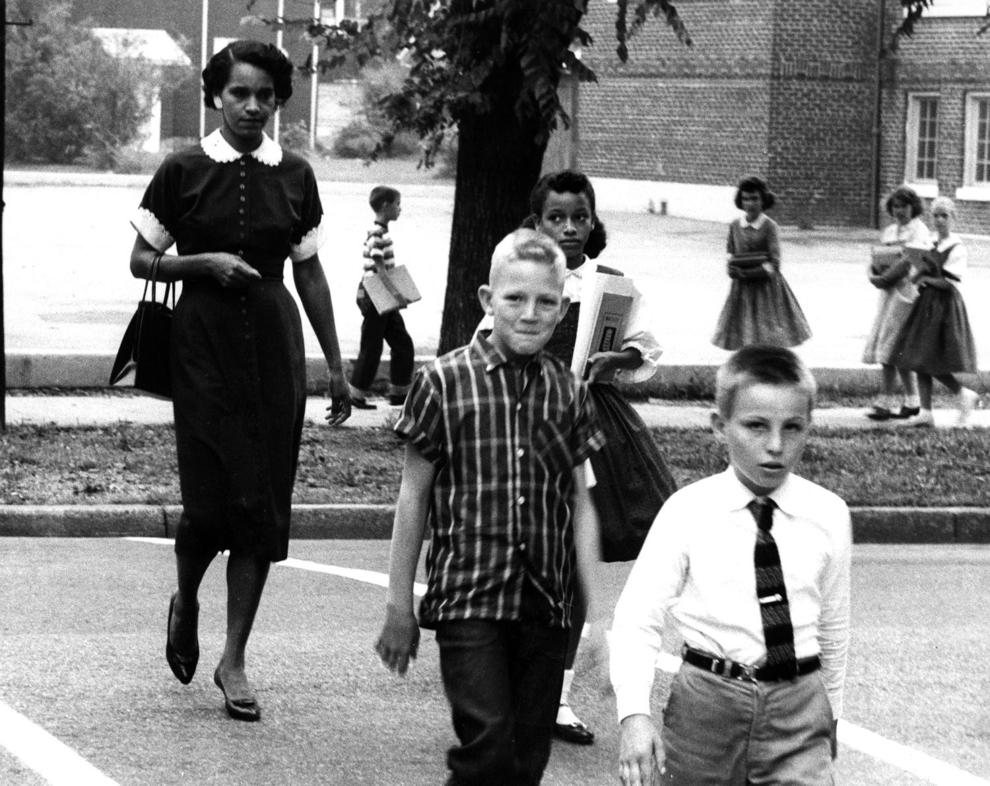

It was not until the Fall of 1960 that nine Black students (of the 39 who had applied to the State Placement Board) were allowed to attend three White schools in Roanoke (Melrose Elementary, West End Elementary, and Monroe Junior High School).

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke

Even that accomplishment had come with substantial perseverance and protest. Years earlier in 1956, the Roanoke NAACP began strategizing to bring about desegregation. The organization elected attorney Reuben Lawson its president, and within a year Lawson contacted the State NAACP for intervention.

In 1962, represented by Lawson, the NAACP filed a suit against the Roanoke School Board (Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke) for 28 Black students who had applied for transfer to White schools, but were not placed in them. The U.S. District Court ruled against the suit, but the decision was overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit. That Court found that “all initial assignments of children enrolling in the city’s school system are on a completely racial basis…Steps must be taken to end the unlawful initial assignment arrangement that exists…It is a racially discriminatory application of assignment criteria.” The Roanoke City School Board was ordered to advance integration.

Over the next few years, more grades were integrated, although attendance lines continued to restrict students eligible to attend White schools. By 1966, the City proclaimed it had completed its court-ordered integration plan and the school system was integrated. Black leaders continued to protest the slow pace of integration, advising that the attendance zones were drawn for racial separation.

In 1969, an integration plan was finally approved by the U.S. District Court, as directed by Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke. In 1970, however, attorney George W. Harris Jr. and the Virginia NAACP filed an appeal which reversed the approval of the school plan and continued court proceedings on the City’s integration plan. Chief Judge Dalton in his case summary advised:

“The school board and this court have been directed to explore every reasonable method of desegregation, including rezoning, pairing, grouping, school consolidation, and transportation, including a majority to minority transfer plan.”

After in depth study and consideration by the School Board and the Court over the next two years, Roanoke schools were fully integrated by 1971. Unfortunately, the court remedy called for closing Booker T. Washington Junior High School (675 students) and Harrison Elementary School (570 students). Black students were divided and transported by bus to other elementary and middle schools outside of Gainsboro. The new Addison High School remained open, but was converted to a Middle School with a student body that was two-thirds white.

Sources

Allen, J. & Daugherity, B. (2021, February 09). Green, Charles C. et al. v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia. In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/green-charles-c-et-al-v-county-school-board-of-new-kent-county-virginia.

Benjamin, N. R. (2022, January 5) Rev. Dr. Raymond R. Wilkinson, Roanoke, Virginia’s Civil Rights Pioneer. https://www.rrwilkinson.org/

Berrier, R. & Chittum, M. (May 26, 2016). Roanoke Reborn. Discover History and Heritage Magazine. The Roanoke Times.

Brown Foundation. (n.d.). Combined Brown Cases 1951-1954. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://brownvboard.org/content/combined-brown-cases-1951-54.

CaseLaw Access Project, Harvard Law School. (2019, August 29). Green v. School Board of the Roanoke, 304 F.2d 118 (1962). https://cite.case.law/f2d/304/118/?full_case=true&format=html

Duignan, B. (2021, 10 August). Plessy v. Ferguson. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Plessy-v-Ferguson-1896.

Edds, M. (2018). We Face the Dawn. University of Virginia Press.

Ellis, S. (2011, May 28). Roanoke’s School Integration: ‘I tried to look like everyone else.’ The Roanoke Times.

Hill, O. W. (2000). The big bang: Brown vs board of education and beyond : the autobiography of Oliver W. Hill, Sr. Four-G Publishers.

History.com Editors. (2022, January 11). Brown v. Board of Education. A&E Television Networks. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka

Jones, P. C. (2013, May). Integrating the Star City of the South: Roanoke school desegregation and the politics of delay. [Master’s thesis, The College of William and Mary] https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6051&context=etd

Justia U.S. Supreme Court. (n.d.) Green v. County Sch. Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). Accessed February 9, 2022, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/391/430/

Justia U.S. Supreme Court. (n.d.) Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 316 F. Supp. 6 (W.D. Va. 1970) Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/316/6/1951461/

Justia US Law. (n.d.) Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 330 F. Supp. 674 (W.D. Va. 1971). Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/330/674/2126324/

Justia U. S. Supreme Court. (n.d.) Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) Law. 1896. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/163/537/

National Archives. (2021, June 3). Brown v. Board of Education. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/brown-v-board

Poff, M. E. (2014, March 17). School desegregation in Roanoke, Virginia: The black student perspective [PhD Dissertation]. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

White, C. (1982). Roanoke 1740-1982. Roanoke Valley Historical Society. Hickory Printing, Roanoke, Virginia.

Benjamin, N. R. (2022, January 5) Rev. Dr. Raymond R. Wilkinson, Roanoke, Virginia’s Civil Rights Pioneer. https://www.rrwilkinson.org/